The Trygon Factor / The Mystery of the White Nuns must rank as the most unusual of the Preben-Philipsen / Rialto film Edgar Wallace krimis. It’s not just the British director, The Witches' Cyril Frankel, and predominantly British cast, but almost the whole structure of the film. For in addition to incorporating giallo and superspy / comic book elements, the film repeatedly plays with familiar krimi film tropes in thoroughly unexpected ways that leave one wondering what exactly was intended and whether some of those involved might even have been at cross-purposes with one another.

What, no Edgar Wallace?

The opening pre-credits sequence sets this out quite nicely: It’s established that London is being plagued by a series of audacious heists that have left Scotland Yard baffled, until now. One of Superintendent Cooper-Smith’s (Stewart Granger’s) men, Sergeant Thompson, believes he has a lead and has gone to a country home, Emberday, to meet up with his contact, Sister Claire (Diane Clare).

The titular family are old, respectable and moneyed – albeit perhaps not as wealthy as they once were, assuming they have not let part of their home be used by the nuns out of philanthropy alone...

Who says nuns have no fun?

The Sergeant is right to be suspicious, all the more so when he happens to notice some of the nuns taking part in a cheesecake style photo-shoot with Trudy Emberday and finds his ‘innocent’ look around the grounds attracting excessive attention.

Unfortunately, having also been spotted by some of the other nuns talking with Sister Clare, he has also clearly learnt too much and is thus murdered by a black-clad, masked assassin who drowns him, with appropriate impiety, in the font.

Giallo murder #1

So far, so krimi, except for the way that the story then continues is by identifying each and every one of the criminal gang for us; suffice to say that the mystery of the white nuns isn't.

Consequently, rather than being aligned with Cooper-Smith as he continues the investigation – why did Thompson’s body turn up in Wapping, some fifty miles away and why did his lungs contain fresh rather than Thames water being the first of the many questions; the link between the convent’s pottery factory and its London-based distributors the next – we are positioned more as external observers watching a game of move and countermove between the gang and Scotland Yard.

The times they are a changing

Besides the appearance and modus operandi of the murderer, with another victim later being drowned in the bath in a possible Blood and Black Lace reference, another giallo-esque aspect is a belatedly revealed – and thus none too effectively incorporated, except retrospectively in playing spot the perhaps lesbian-coded man-hater – element of gender confusion that wouldn’t have been too out of place in the likes of Four Flies on Grey Velvet.

Done with mirrors

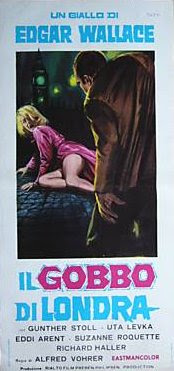

The comic book or superspy aspect comes into play through the presence of Eddi Arent, as the sole krimi regular within the cast of the English-language version under review here. He plays a Continental safecracker smuggled into the country to help the gang penetrate an otherwise impenetrable safe with his rocket gun whilst wearing a yellow armoured suit, these being two pieces of apparatus that wouldn’t look out of place in Diabolik or Fantastic Argoman.

Arent goes to work

Another thing that is unusual here is the fate that befalls Arent’s character, along with the other men recruited for the job: It’s 'just not cricket,' a far cry from the usual Wallace criminal organisation that demands and rewards its members’ loyalty.

This said, the gang’s betrayals do feature another Wallace staple, namely the vehicle with the rear gas fill-able compartment, one of those elements that, if prefigured in Fritz Lang’s Weimar films, I’ve often wondered about in the post-WWII krimi in relation to the Einsatzgruppen of the intervening period...

In a similar manner the nuns’ order seems characteristic of Wallace’s treatment of religion and charitable organisations, modulating what might be seen as an attack on the former – i.e. a convent of criminal nuns – by foregrounding the latter – i.e. that these nuns do not represent any real order. Returning to the giallo, it’s a bit like the plethora of films there that feature fake or defrocked priests as killers, compared to the relative minority with actual killer priests, a have your cake and eat it strategy that lets the viewer take the message they want from the text.

Giallo murder #2

The marriage trajectory of the typical krimi damsel in distress is also spoofed somewhat, with the suave, droll and self-deprecating Cooper-Smith romancing a French hotel worker young enough to be his daughter and who quite candidly admits to being on the lookout for a wealthy English husband.

If the role of Luke Emberday, the obligatory upper-class twit cum madman who ought to be in the attic, cries out for Klaus Kinski, Robert Morley makes for a more than satisfactory Werner Peters stand-in as the ever-nervous Hubert Hamlyn, manager of the pottery’s distribution arm.

The Trygon, by the way, refers to the distinctive (de)mark on some of the pottery, three triangles (representing the three stated aims of the convent) which together enclose/delimit a fourth and create a fifth, that the gang uses to transport their ill-gotten gains and which perhaps recall The Lavender Hill Mob, or vice-versa, given the 1928 date of Wallace’s original novel, Kate Plus Ten.

In summary, an atypical krimi that may be best appreciated / approached by those already familiar with the more conventional aspects of the form.